Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc.

Volume 55, No.3 - Fall 2009

Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas.

LITHUANIAN

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES

|

ISSN

0024-5089

Copyright © 2009 LITUANUS Foundation, Inc. |

|

Volume 55, No.3 - Fall 2009 Editor of this issue: Gražina Slavėnas. |

The Road of a Thousand Years

ZIGMANTAS KIAUPA

Zigmantas Kiaupa is Professor of History at the Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas and Senior Researcher at the History Institute in Vilnius. He is editor-in-chief of the history annual “Lietuvos istorijos metraštis” and author of several books and numerous articles.

ABSTRACT

One of Lithuania’s foremost historians traces the thousand

years traveled by Lithuania from Netimeras’s clansmen to the

contemporary state reestablished in 1990 in a European context as an

assembly of citizens. Kiaupa refutes arguments that the modern

Lithuanian state established in 1918 had no continuity with the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania which expired in 1795, or that it was their language

rather than their political convictions that made Lithuanians a true

nation, as suggested by Czesław Miłosz. His thesis is that the modern

Lithuanian state reestablished in 1918 was the result of complex

ethno-cultural and political factors involving representatives from

various political and social classes, based on national unity rather

than mere language, and with a definite connection to the historic

past. Lithuania has changed many times, becoming a different nation,

but not another nation. Geographically, it exists in the same place,

and linguistically, its residents still speak the same language. In

other words, contemporary Lithuania and the Lithuanian nation are

directly descended from the eleventh-century Lithuania of Netimeras and

the Lithuanians of that time.

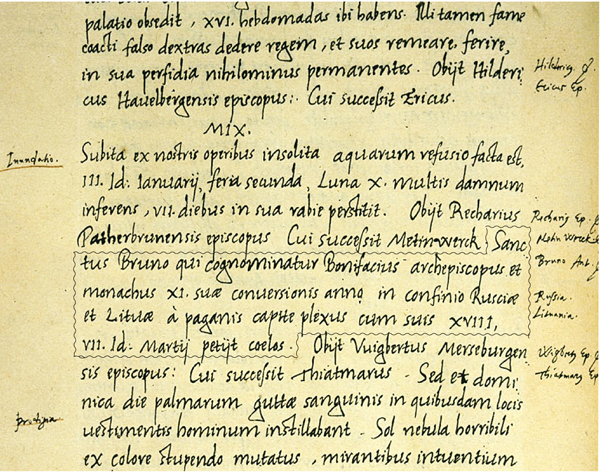

Lithuania’s name was recorded for the first time in the first half of the eleventh century in the annals of the Quedlinburg monastery (Annales Quedlinburgenses). It was mentioned in a narrative describing the mission of Bruno, the future saint, to pagan lands, and his death by martyrdom. In 1009, Bruno and his entourage reached the borderlands of Rus’ and Lithuania. There he succeeded in converting the pagan rex [ruler, king] Netimeras and his people to Christianity, but was martyred by some of Netimeras’s clansmen who refused to be baptized.

|

From

the Quedlinburg Annal for 1009. “St. Bruno, called Boniface, an

archbishop and monk, during the 11th year of this conversion, at the

Rus and Lithuanian border, was struck in the head by Pagans, and along

with 18 of his followers entered heaven on March 9th.” Accessed at http://digital.slub-dresden.de/sammlungen/werkansicht/287626156/64/#view |

Of the entire series of eleventh-century sources dedicated to St. Bruno’s missionary work and life, only the Quedlinburg annals and the chronicle of Thietmar of Merseburg (Thietmari Merseburgensim episcopi Chronicon) make any mention of Lithuania.1 In other sources, Lithuania is construed as part of the broader concept of Prussia, which was more familiar to the Christian missionaries of the period. For a time, the predominant historical view was that Bruno’s death occurred in Prussia, but after World War II a more carefully researched opinion came to the fore that claimed Bruno had baptized Netimeras and was slain in the borderlands of Lithuania and Rus’.2 An analysis of the place names in the St. Bruno series of sources undertaken in recent years also supports the view that St. Bruno’s activities took place in one of these border areas in Lithuania.3 The fact that the other country of the borderlands, Rus’, was already Christianized and its ruler did not have to be baptized gives even more credence to this argument.

At the present time, as we mark the millennium of the first documented reference to the name of Lithuania, the Lithuania that we live in and visit is obviously completely different from that of Netimeras’s and St. Bruno’s time. I am not talking about advances brought about by the inevitable progress of civilization and culture, such as the development of written language following Lithuania’s Christianization in 1387, firearms, the internal combustion engine, electricity, the Internet or the nuclear reactor now being decommissioned in Ignalina. Numerous other phenomena could be added to the list. Rather, what I am referring to is the structure of Lithuanian society and the Lithuanian state itself: the structure of the Lithuanian nation.

The parameters of Lithuania and the Lithuanian nation have undergone fundamental changes over the millennium, but their defining characteristics have remained conditionally constant. Lithuania is found in the same spot on the globe as it was a thousand years ago, and Lithuanians speak the same language. But even these features, as already mentioned, are only conditional, because the borders of Lithuania’s territories have shifted, and the Lithuanian language, as all the world’s living languages, continues to evolve.

The greatest and most essential transformation has occurred in the structure of the Lithuanian ethnic community and its organization within the surrounding circle of its close and distant neighbors. Netimeras, a leader of the early eleventh-century Lithuanians, obviously led only one of the clans. Even though he ruled with a strong hand, in decisions of the greatest importance he had to conform to the wishes of other clan leaders. In the series of sources we have on St. Bruno, especially the hagiographical works, Netimeras is consistently called rex. However, it would be a mistake to take this term literally to mean the equivalent of a Christian king.4 At the beginning of the eleventh century, Netimeras’s Lithuania existed only in a condition of pre-statehood. More complicated questions are: to which territory was the name Lithuania ascribed, and how large was the ethnic population of that territory? Did Netimeras rule all or only part of Lithuania? The series of sources on St. Bruno suggests the latter. These domains were in Lithuania’s borderlands with Rus’, and stretching beyond them there were surely other Lithuanian lands. We know that the Lithuanian language broke off from the splintering body of the Baltic peoples around the seventh century,5 and that its speakers inhabited a relatively large area extending over the greater part of the Nemunas river basin.

We have no available facts to support a discussion of how the basic aspects of Lithuanian life circa 1009 may have changed. Therefore, when we speak of Lithuania’s internal social, political, or other development, the year 1009 represents merely a symbolic date signifying the first mention of Lithuania’s name. To be sure, looking at this fact from the standpoint of Lithuania’s recognition within Europe, one could say that this was a pivotal moment in Lithuania’s history. Lithuania’s name, which was little known and rarely spoken, or perhaps just did not exist in written documents, entered Europe’s consciousness, albeit very tentatively as yet.

* * *

The territories of the Lithuanians underwent a drastic transformation from the end of the twelfth to the middle of the thirteenth century. Up until then, Lithuanian lands had been the object of neighbors’ expansionary designs, the Church’s Crusades, or predatory military raids. But during this time, according to Rus’ annals and the chronicles of Lithuania’s western neighbors, Lithuanians themselves began to launch campaigns into the lands of Rus’ and into the lands of their Baltic kin, especially northward into Padauguvys in today’s southeastern Latvia. Here in the early thirteenth century Lithuanians confronted the official institutions brought by the German colonists – the diocese/archdiocese of Riga and the Brothers of the Sword. This marked the start of hostilities between the Lithuanians and these new forces in the region. In 1237, the Brothers of the Sword were absorbed by the Teutonic Order and became known as the Livonian Order. By the end of the thirteenth century, the Teutonic Order had defeated the Prussian tribes and entered into a war to conquer Lithuania. The protracted conflict between Lithuania and the Crusaders began.

The campaigns of the Lithuanians were proof of their advanced military prowess and of the changes taking place in their organized society, which was developing from one based on clans to pre-statehood. The latter process continued over many decades and most likely experienced periodic setbacks. The formation of the Lithuanian state is not well documented, so it is not surprising that there are several hypotheses as to its creation.6 In any case, Lithuanian lands (in the narrow sense) were finally unified in the period 1220-1240 under Duke Mindaugas. Around the late 1230s or early 1240s the Lithuanian state was born.

Soon thereafter the Lithuanian state became embroiled in its first regional multi-national conflict, which involved Mindaugas, his domestic enemies, the Rus’ princes of Galich-Volyn’, the Livonian Order, the Archbishop of Riga, and, indirectly, the Pope in Rome. Mindaugas resolved the crisis in 1251 by accepting baptism, and in 1253 he was crowned king. As the conflict with the Catholic political forces of Livonia escalated, he had to face pagan reaction, and in 1263 Mindaugas was slain. But his state, even though it went through a difficult period, endured.

Lithuania, compared to what it was at the beginning of the eleventh century, had assumed a new guise. At first, Mindaugas was the ruler of Lithuania proper, or the narrowly construed Lithuanian territory delimited by the interstices of the Nemunas and Neris Rivers. He succeeded in bringing other Lithuanian lands under his control – Nalšia; Deltuva; the lands of the Neris; and Žemaitija (Samogitia) – which could be themselves subdivided into smaller units. After being unified under one ruler, the mass of Lithuanian lands, which had been in transition from a clan to a state structure, took on the form of a state. This, no doubt, spurred the consolidation of the Lithuanian clans into a more close-knit ethnic society, a nation.

The state that Mindaugas assembled and ruled for around twenty years was the first Lithuanian state. It was Lithuania’s destiny, because of its geopolitical situation, to hold back the encroaching threat of the Teutonic and Livonian Orders, as well as the Crusaders’ campaigns. At the same time, it had to take the lead in the lands of Rus’ and expand the state’s territory eastward. In the Lithuania of Mindaugas and his successors, three worlds collided – pagan Lithuania, Catholic Europe, and Orthodox Rus’ – each different in its worldview, its state-building, and so on. Mindaugas sought to integrate all three, but failed due to the western world’s indifference to the interests of Lithuania and the other Baltic peoples. His attempt served as a warning to future generations of Lithuanians and their rulers. This unfortunate circumstance resulted in the prolonged isolation of the still-pagan Lithuania from Europe and its cultural development, making it the object of forced Christianization and western aggression.

A comparison of the Lithuanias of the early eleventh and thirteenth centuries and an examination of their differences – not only in terms of their social development but also their political structure – leads to the question of whether there is any connection between these two Lithuanias. Historical sources do not provide any clues as to whether or not there is a direct link between Netimeras’s Lithuania and the narrowly construed Lithuania proper or some other Lithuanian domains. Nevertheless, the early-eleventh-century Lithuanians were undoubtedly the ancestors of the thirteenth-century Lithuanian nation that united or was unified into one state. At the same time, the fact that various Lithuanian clans now constituted the state and that social stratification was clearly taking place proves that the Lithuanian nation of the thirteenth century was fundamentally different from the Lithuania of the eleventh century.

* * *

The political situation of Lithuania from the end of the thirteenth through the entire fourteenth century impelled the Lithuanian rulers of the Gediminas dynasty to push into the Rus’ regions that stretched to the East. The scattered and politically weak principalities of western Rus’ one after the other were incorporated into the Lithuanian state. By the turn of the fifteenth century the lands of Rus’ represented 80 percent of the territory of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, and ethnic Lithuanians were a minority. These facts, coupled with the fanciful idea that the princes of Rus’ surrendered willingly and without the use of force, provided the basis for the persistent nineteenth-century historiographical theory that the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was a Lithuanian-Rus’ian or even a Rus’ian-Lithuanian state.7 According to this interpretation of history, Lithuania’s rulers acquired the principalities of Rus’ in order to unify Rus’.

Feeding this theory is a statement made in 1358 by Grand Duke Algirdas (1345-1377) that Rus’ in its entirety should belong to him. In fact, Algirdas and other Lithuanian rulers, by mounting campaigns into the lands of Rus’, were attempting to subjugate them. In other words, those lands were not being unified into an independent political entity, but were being incorporated into the Lithuanian state. One widely held view suggests that the majority of these lands were taken peacefully, without resistance. The dukes of the Gediminas dynasty were charged with administering them and, at first, efforts were made to leave intact the social structures and local norms that had existed within the annexed lands.

These circumstances were considered sufficient evidence to support the claim that the Lithuanian state from the fourteenth through the sixteenth century was a Lithuanian-Rus’ian state. Nonetheless, together with its defenders and proponents, this theory also has its detractors. Without going into a deeper discussion about the beginnings of Lithuania’s Grand Duchy, it would be worthwhile to mention briefly several notable historical studies of more recent years. Stephen C. Rowell, in his work on Lithuania in the first half of the fourteenth century, calls it a “pagan empire.”8 Accordingly, Lithuanians conquered the lands of Rus’ by force and afterwards, having loosened their constraints, they maintained power by means of complex diplomacy and dynastic marriages.9 With the Lithuanian ethnic lands as their bulwark, the Lithuanian rulers ensured pax lituanicum, i.e., safe passage for people and goods throughout the entire far-flung state.10

Zenonas Norkus uses the concept of “empire” to explain the relationship of the Lithuanian state’s Lithuanian and Rus’ian lands from the fourteenth through the first half of the fifteenth century.11 Lithuania engaged in aggressive expansionary politics, pressing militarily in those directions where it would not be stopped by superior forces. One must agree with the author that Lithuania’s penetration into the lands of Rus’ was not a peaceful expansion.12 It is true that at times one or another principality of Rus’ would be taken without military force. Sometimes this would occur “peacefully,” but the conqueror always had a sword by his side, even if the sword was never drawn.

Another of Norkus’s “imperial” arguments is that the Lithuanian state comprised two distinct regions: the nucleus or metropolija and the outlying areas, ukraine or periferija.13 The state’s Lithuanian lands made up the nucleus or metropolija, while the lands of Rus’ represented the periferija. These parts of the state differed: first, in the ethnicity of their inhabitants; second and even more important, in their confession (Lithuanians were pagans and, from 1387, Catholics, the Rus’ were Orthodox); and third and most important, in their participation in the government of the state. At the center of the Grand Duchy’s ruling elite was the Lithuanian nobility, one of the state’s ethnic bodies. Historical research clearly shows that, after Lithuania’s Christianization in 1387, the newly baptized Lithuanian nobility was granted special privileges to participate in the life of the state. The political classes of the Orthodox lands (with the exception in the fifteenth century of a very small number of dukes of the Gediminas dynasty) did not participate in governing the Lithuanian state, not just in pagan times but all the way up to the early sixteenth century, when the Council of Lords that shared power with the Grand Duke gained its first Orthodox member.

One must emphasize that the lands of Rus’ contained within the Lithuanian state did not constitute a monolithic entity that could be juxtaposed against the state’s nucleus – the Lithuanian lands. The Lithuanian state’s Rus’ian lands shared a common religion and a common past as part of Kievan Rus’. But in the interim period between the Kievan state and the Lithuanian state these principalities had stood separate and alone, evidence that in the Kievan state the process of integration, and this was from an ethnic standpoint as well, had not been completed. In the fourteenth century, Lithuania occupied and later ruled Volyn’, Polotsk (of the Krivich tribe), Kiev, Smolensk and other Rus’ian lands, but these were not a homogeneous political and ethnic body. The efforts of Lithuania’s rulers to have a metropolitan of the Orthodox faith within the state, i.e., an institution that would strengthen their rule in all of Rus’ and also unify the Rus’ian lands, brought about only temporary results and were not effective.14 The ties that each of the Rus’ian lands had with Lithuania’s rulers were more significant to them than any of the ties that they shared among themselves, which, nonetheless, did exist.

Thus, the Lithuanian state from an ethno-confessional standpoint comprised Lithuanian Catholics and Rus’ian Orthodox. In the lands of the latter the internal consolidation leading to the formation of a state was not yet complete. But the Lithuanian state, even after it had incorporated the vast expanse of Rus’ian lands, remained a Lithuanian state. Its leading members were the Gediminas dynasty, the Jagiellonians that separated from the latter, and the upper classes of the Lithuanian nobility, who at the turn of the fifteenth century, during Vytautas’s rule (1392-1430), had risen to the state’s highest government positions and soon constituted the class of lords. By the beginning of Jagiellonian rule in Lithuania (1440-1572), the Council of Lords had succeeded in positioning itself alongside the rulers as the representative of the interests of the Lithuanian state within the central government. While one may speak of a Lithuanian-Rus’ian state in terms of its ethno-confessional composition and its ethno-cultural features, the state was a decidedly Lithuanian state from a political standpoint.

This Lithuania was also different from that of Netimeras and Mindaugas. The territory had grown; the society’s structure had evolved. The concept of Lithuanian identity had changed, as, alongside its ethnic and confessional characteristics, the state itself came to the forefront as an increasingly important identifying factor. Within the bounds of ethnic culture, the Lithuanian political nation had begun to form. At its core in the early sixteenth century were the upper strata of the nobility, the lords who as early as 1501 had proclaimed Mes, Lietuva [We, Lithuania].15

* * *

In the sixteenth century the intensive socio-economic, political, as well as cultural changes taking place in Lithuania were also transforming the nobility, who represented the body politic. All classes of the nobility gained prominence within the central government of the state. They grew strong economically and sought expanded and even equal privileges with the lords. During the first decades of the sixteenth century the power and influence of the nobles increased, as evidenced by the Grand Duchy’s Parliament (Seimas) of Nobles, the First Statute of Lithuania promulgated in 1529, and the land courts of the nobility established in the early 1540s. The political and social reforms of 1564-1566, together with the Second Lithuanian Statute enacted at that time, transformed the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into a body politic that comprised the entire nobility.

Another important trend was the completion of the process begun during the reign of Žygimantas Kęstutaitis (1432-1440) that granted equal privileges to both Catholic and Orthodox nobles. The above-mentioned sociopolitical changes occurred throughout the entire realm, bringing about the gradual and inevitable inclusion of Orthodox nobles into the functions of the state. Furthermore, the Reformation, which was gaining strength in mid-sixteenth-century Lithuania and attracting not only former Catholics but also some Orthodox, chipped away at the barriers between Lithuanian/Catholic and Rus’ian/Orthodox nobles. “Mes, Lietuva” was a call that could be and was proclaimed by all the nobles of the Lithuanian state, regardless of their ethnic background or their Christian confession.

This then was the Lithuania that in 1569 entered into the Union of Lublin with Poland. A joint Polish and Lithuanian state, contemporaneously called the Republic of Both Nations, was created and existed until 1795. The Republic comprised two equal states and was ruled by two national political bodies of nobles, those of Lithuania and Poland. They shared in common an elected ruler and a Parliament of Nobles. Both states maintained their territorial sovereignty and had their separate treasuries, armies, and highest state officials. Their foreign policy was supposed to be unified and indeed it was, though with exceptions. Domestic policies were subject to separate laws in each state, though there were some uniform measures, especially in those areas affecting foreign policy (e.g., taxes for military purposes).16

Therefore, one cannot agree with the nineteenth-century Lithuanian historians Teodoras Narbutas and Simonas Daukantas that the history of the Lithuanian state ended in 1569, or with the major trends of Polish historiography during the nineteenth and through the first half of the twentieth century that unequivocally equated the Republic of Both Nations with Poland. In recent decades, historical research in Poland is experiencing a fundamental change, perhaps best represented by the work of Juliusz Bardach, who regards the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as an equal member with Poland in the Republic of Both Nations.17 This concept now has gained validity in western historical research, which for a long time had been influenced by the older Polish view. Evidence of this trend is the use of the term “the Polish and Lithuanian state” rather than “Poland” to designate the joint state.18

Throughout the existence of the Republic of Both Nations, a closer association naturally developed between the nobility of both states and their national political bodies, especially since their basic structures were analogous. This process was predestined by their common concerns regarding the Republic, the state’s increasingly precarious position among ever stronger neighbors that spurred closer cooperation, expanding family ties among the nobles and especially the magnates of both states and the related property issues, as well as the status that Polish achieved in Lithuania as the official language of communication. In these developments one can see the formation of a political macro-nation of the Republic’s nobility. However, it is entirely clear that, up until the end of the Republic in the last years of the eighteenth century, such a nation had not been formed and that the nations of Lithuania’s and Poland’s nobility did not coalesce into one.

There also were internal differences within the body politic of the Lithuanian nobility itself. The Rus’ian nobles had begun to use Polish exclusively as their common language, and present-day research does not indicate that they were bilingual. The nobles of the Lithuanian lands, on the other hand, had not forgotten the Lithuanian language, even as late as the eighteenth century. In the public arena, though not at church, Polish inarguably dominated. But the majority of the Lithuanian nobles were bilingual. Polish was their primary language in public life, but at home or in dealing with their subordinates, they spoke Lithuanian. As evidence we see the voluminous editions of Lithuanian primers that came out in the eighteenth century. Published in Vilnius during 1759-1791 were fourteen editions, often numbering thousands of copies, of a primer intended for the children of nobles and peasants entitled Mokslas skaytima raszta lietuwiszka (Lithuanian reading lessons).19

During 1569-1795 we begin to see a Lithuanian state and a Lithuanian nation that have assumed still another new guise. Alongside the changes in the territory of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy, there were even more important changes in terms of its existence as a state. Lithuania formed a union with Poland, but it did not disappear within the Republic of Both Nations created by the union, nor into the union’s partner, Poland. Lithuania and Poland were members of a federation and each retained all the features of a state.

To speak of a Lithuanian nation during this period is a very complicated matter. Concurrently, we had both an ethnic nation and a political nation, which did not coincide. The political nation of the nobility was multilingual (Lithuanians, Rus’ians, transplanted Poles or Germans) and multiconfessional (Catholics, Orthodox, Protestants, Uniates). It comprised one of the social classes of that time, which ruled and represented the Lithuanian state. At the same time, there existed the ethnic population, the ethnic nation, which was composed of members of all the social classes – nobles, peasants, and townspeople – who were of Lithuanian descent. The majority of them spoke Lithuanian.

With the state’s governing power concentrated in the hands of the nobility, i.e., a numerical minority, the great majority of the Lithuanian nation found itself on the fringes of the political life of the state. This slowed the consolidation of the Lithuanian nation, since the conditions necessary to this natural process were largely inadequate. The most vivid example of this deficiency was the exclusion or very limited use of the Lithuanian language in public life. This obviously inhibited the development of the language and discouraged its potential use by all of Lithuania’s social classes as the everyday language of communication.

What was needed was some kind of a catalyst or a confluence of events that would thrust the Lithuanian language into public life. This is exactly what occurred in the waning days of the Republic, during the insurrection of 1794. The highest office of Lithuania’s government, the Supreme National Council, spoke out in Lithuanian. It declared manifestos that set forth the aims of the uprising and urged all to join the struggle against Russia, which had occupied the state.20 The manifestos were addressed to all the social classes – nobility, peasants, and townspeople.

This effective leap of the Lithuanian language into the public sphere was short-lived, as was the uprising of 1794 itself. The Third Partition of the Republic in 1795 wrought profound changes on Lithuania’s political situation and on its future cultural development.

* * *

For more than a hundred years, from 1795-1918, Lithuania remained a part of the Russian Empire (the lands on the left bank of the Nemunas were added in 1815; from 1915-1918 Lithuania was occupied by Germany during its war with Russia). This long period, which lasted throughout almost the entire nineteenth century, was a time of intensive change affecting both aspects of the Lithuanian nation: the body politic of the nobles and the ethnic nation.21 The political nation of the nobility, deprived of the state, did not disappear. Some of them collaborated with the Russian government, others assumed a conformist stance, but the majority promoted the idea of the re-establishment of the Lithuanian Grand Duchy together with Poland, i.e., the Republic of Both Nations. They attempted to realize this goal by resisting the Russian Empire in various ways, including social-cultural activity in public life in addition to political conspiracy. The major revolts against the Russian Empire were the uprisings of 1831 and 1863, which were organized by the nobility.

The loss of their state brought the nations of the Lithuanian and Polish nobility even closer. In the insurrections they rose up together and sought the same goal: to reestablish their state. The uprisings were the mutual undertaking of the two political nations of the former Republic of Both Nations. However, in the eyes of contemporaries, they assumed a Polish garb and were called a “Polish uprising,” with the Lithuanian nobles fighting for “Poland.” Decisions regarding the future of Lithuanian and Polish relations were deferred until after the insurrection, and there were numerous suggested models for this future relationship. For example, simplifying greatly, one might say that the “Whites” of 1863, with Jokūbas Geištoras at their head, saw Lithuania as a province of Poland; Antanas Mackevičius saw it as an equal partner in a federation; Konstantinas Kalinauskas or Jokūbas Daukša sought a separate Lithuanian state; Bishop Motiejus Valančius and his circle promoted a free ethno-cultural existence.22

The above-mentioned first tendrils of the “Lithuanization” of Lithuania’s socio-political life that appeared at the end of the eighteenth century truly should be seen only as tendrils, especially since they failed to thrive once the state collapsed. But the cultural Lithuanian movement that was born during the first decades of the nineteenth century continued all the way up to the reestablishment of the Lithuanian state, even though the focus of its interest, as well as its participants and their aims, changed over time. Initially it was a product of the Romantic Era, which inspired the nobility to cultivate an active interest in the Lithuanian language, folklore, and history, as well as the use of the Lithuanian language in writing literature and religious texts.23 Lithuanian peasants, or the so-called folk (Volk), became involved in this initial stage of the movement, but more as passive participants, i.e., as the most consistent users of the Lithuanian language, as the communicators of folklore.

The middle of the nineteenth century might be called the epoch of Motiejus Valančius (1801-1875), who was the rector of the Theological Seminary at Varniai in Žemaitija (Samogitia) from 1845-1850, and who was consecrated bishop in 1850.24 At this time, the cultural Lithuanian movement flourished at an informal level among the Lithuanian nobles and the common folk. Under the conditions of serfdom and the Russian Empire’s regime, Lithuanian culture became multilayered in terms of social classes and in terms of the direction and range of cultural activity. It turned its attention toward the ordinary folk: the peasantry, petty nobility, and townspeople. Published for their benefit and in the Lithuanian language, alongside the usual prayer books and primers, were booklets of practical advice and calendars with didactic texts. At the same time, one can see the beginnings of an elite Lithuanian language (the historical works of Simonas Daukantas and Motiejus Valančius, the botanical studies of Jurgis Pabrėža). We also find a Polish-language culture that, nonetheless, was emphatically Lithuanian from a political standpoint (Teodoras Narbutas, Liudvikas Jucevičius and others).

Crucial changes in the development of the Lithuanian nation resulted from the abolition of serfdom in 1861 and the squelching of the 1863 uprising. The road to legal and cultural emancipation was opened up to the peasant masses after the abolition of serfdom; the suppression of the insurrection was a major blow to both Poland’s and Lithuania’s nobilities and to their traditional political power. Those elements of the nobility that held on to the former Republic’s traditional ethno-political ideas of union came face to face with other Lithuanian socio-political movements. One sees the first signs of the Lithuanian noble classes splitting along Polish or Lithuanian lines. The uprising of 1863 represented the sunset of the consolidated body politic of the Lithuanian nobility, which was supplanted by a Lithuanian nation of a different aspect.

This nation comprised all social classes, and perhaps its most important distinguishing feature was the Lithuanian language. This nation was formed by Lithuanian peasants who became actively involved in social and cultural life, and by the intelligentsia whose roots were in the peasantry. The gains derived from nineteenth-century Lithuanian-language cultural activity provided a foundation for the further promotion of this culture, despite repression by the Russian government. The essentially agrarian folk character of this cultural movement and its ethnic, not political, Lithuanian aspect naturally directed it not only against Russification, but also against manifestations of ethnic and political Polonization.

The day of reckoning had arrived for the nobility, for townspeople who had lost their ties to the Lithuanian language, for the lay intelligentsia and for the clergy. They needed to decide who they were – Lithuanians or Poles. This question gained even more relevance at the end of the nineteenth century, when Lithuanian political parties began to form and to promote ideas regarding the reestablishment of the Lithuanian state at the same time the Polish nation was moving toward reestablishing a state.

It was a complicated situation for the Polish-speaking nobility and individuals of the educated classes, who were still promoting the values of the nobility’s political nation while maintaining their conviction that they differed from the Polish nation. They did not equate themselves with the Poles and considered themselves to be citizens of the former Lithuanian state, which was being replaced in their eyes by the new Lithuanian-speaking Lithuania. Some of them moved with determination toward the ethnic Lithuanian side, others viewed themselves as Polish-speaking Lithuanians, and still others, while calling themselves Poles, considered Lithuania, not Poland, to be their native land. These groups of people participated in Lithuanian cultural and political life, supporting it or at least not opposing the aims of the Lithuanian national movement.

It was a different situation for those inhabitants of Lithuania, either nobles or townspeople, who with no equivocation identified themselves with the Polish nation. Their destiny was linked with Poland, and they could see Lithuania only as a part of one state with Poland. This position posed a threat to the aims of the Lithuanian national movement and caused cultural and political strains between Lithuanians and Lithuania’s Poles.

In this way, the modern Lithuanian nation began to form with a foundation based on an ethnic Lithuanian sensibility and encompassing various social classes, mostly the agrarian class together with the lay intelligentsia and clergy that it produced, but also including parts of the nobility as well as townspeople, who were still not very numerous at the turn of twentieth century. Their common bond was not only the Lithuanian language, but also political goals, which so clearly manifested themselves during the revolution of 1905. In Lithuania, alongside the political waves of constitutional democracy and the “red” revolution that reverberated throughout all of Russia, there was also the national political wave that overshadowed the others. Its moment of glory was the congress of the representatives of the Lithuanian nation that met in Vilnius in 1905 and entered the pages of history as the Great Assembly (Seimas) of Vilnius.25

This Lithuanian nation within its new guise, though still existing without a state in the “prison of nations,” as the Russian Empire was called, nonetheless was creating its own social, cultural, and political structures. Lithuanian activity permeated all strata of Lithuanian life and all regions populated by Lithuanians. There was a true explosion of Lithuanian culture at the beginning of the twentieth century and one has to agree completely with Vincas Trumpa that Lithuania became culturally independent much earlier than it did politically.26

Another step taken by this modern Lithuanian nation within its new guise was the reestablishment of independence, seizing on the opportunity that presented itself as World War I drew to a close and Europe’s empires in Eurasia and the Middle East collapsed. However, it was not advantageous circumstances but, rather, the modern Lithuanian nation joining forces behind the united front of its ethno-cultural and political goals that made the declaration of the reestablishment of the Lithuanian state on February 16, 1918 both possible and capable of being realized.

The structure of the modern Lithuanian nation that entered the political arena in 1905 and reestablished the Lithuanian state in 1918 essentially has remained unchanged to our day, the beginning of the twenty-first century. Gone now are any traces of social classes harkening back to earlier times; the relationship between rural and urban populations has changed; the educated class or the intelligentsia is increasing both in numbers and in influence within the nation’s life. Yet the nation has remained the home of all social classes of Lithuanians, just as it had when the roles of the Lithuanian ethnic and political nation coalesced into one. This nation is an assembly of citizens equal under the law; it is the body of the Lithuanian state that, during the course of the twentieth century, existed as an independent state and was then erased from the political map of the world for a period of fifty years.

* * *

It is a long road that has been traveled over the thousand years from Netimeras’s clansmen to the contemporary modern nation that was reestablished as its own state in 1990 as an assembly of citizens. I doubt if one can agree entirely with the often-cited statement by Czesław Miłosz that the modern Lithuanian nation is the “fruit of philology,” i.e., that it was the recognition of the significance of their language and not their political convictions that made Lithuanians a true nation. During the nineteenth century, the Lithuanian nation fought for its cultural existence; in the twentieth century it proclaimed its political goals. It began doing so after major social changes had occurred within the nation, and after the new political forces joined with some of the descendants of the old body politic. In other words, a complex ethno-cultural and political movement gave birth to the modern Lithuanian nation. The Lithuanian language was one of the most important tools with which this new nation sought to achieve its political aims, but it was not the only one. No less important in the whirlwind of political battles was social solidarity, or what is called national unity. Of course, there was never perfect solidarity, since each of the nation’s social classes had its own specific interests. But during the nation’s most difficult times, it was possible to coordinate and harness its political goals for the common good of the nation that was being born.

In Lithuania from time to time we still hear reiterations of the thesis that there is no continuity between the political nation of the Lithuanian nobility and the modern Lithuanian nation; that the Lithuanian nobles as early as the seventeenth century had completely lost their national identity and had become Poles; that the Lithuanian state of 1918 did not represent the reestablishment of the old Lithuanian state but was a completely new state with no connection with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania which had expired in 1795.27 But this is not what the signers of the Act of February 16 believed when they asserted that the Council of Lithuania was reestablishing an independent state of Lithuania based on democratic principles, with Vilnius as its capital.28 Note that they did not say “newly created,” but “reestablished.” They were declaring that this state represented the continuation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. They did not go on to explain the essence of the connection, but one can assume that the ties were not only emotional but also historical-juridical, as shown, incidentally, by the fact that they named Vilnius the capital.

The declaration of the Council of Lithuania in 1918 may have been conditioned by the political circumstances of the time. Now, however, at the turn of the twenty-first century, we are not subject to any such constraints. And so, relying on our knowledge of Lithuania’s history and without attempting to modernize the past by applying to it contemporary concepts of nation, we must come to the conclusion that both the Lithuanian nation and Lithuania itself, even as they constantly changed, transitioning from one guise to another, never severed the many connections between those transformations.

Contemporary Lithuania and the Lithuanian nation are directly descended from the eleventh-century Lithuania of Netimeras and from the Lithuanians of that time. Geographically, Lithuania still exists in the same place. Linguistically, its residents still speak the same language. It has changed many times, becoming a different nation, but not another nation.

Translated by Birutė Vaičjurgis Šležas

1. Voigt, Brun von Querfurt.

2. Bieniak,

“Wyprawa misyjna Brunona,” 191-103;

Leonavičiūtė, “Trys ar keturios,” 19-25

3. Savukynas, “Nomina propria,” 13-18.

4. Overall, when considering the information provided by the St. Bruno

sources, especially the hagiographical works, one constantly must

question the sources used by the authors, who were in Bavaria and Rome,

and the information’s reliability, as well as the problem of

stereotyping found in hagiographical works. It is not always possible

to resolve these issues and the assertions of the above-mentioned

sources, which are often accepted word for word. See, for example,

Gudavičius, “Šv. Brunono misija,”

120-123.

5. Zinkevičius, Lietuvių kalbos, 337-340, 376-377.

6 Kiaupa, The History of Lithuania, 28-32. The following is a brief

summary of the principal hypotheses regarding the formation of the

Lithuanian state. Henryk Paszkiewicz asserts that Lithuania was already

unified at the beginning of the thirteenth century, but its rulers

could not stay in power for any length of time (Paszkiewicz, The Origin

of Russia). Tomas Baranauskas asserts that a stable state structure

appeared in the Lithuanian lands around the eleventh century, and the

small Lithuanian state grew larger consistently, becoming the Grand

Duchy of Lithuania (Baranauskas, Lietuvos valstybės

ištakos).

Henryk Lowmiański, Vladimir Pashuto, and Edvardas

Gudavičius, each differing in their interpretation of the level of the

socio-economic development of the Lithuanian lands as well as the

extent and significance of external influences, assert that the task of

unifying Lithuania fell to Mindaugas, the duke of Lithuania proper

(Lowmiański, Studija nad pocątkami, Pashuto, Obrazovanije litovskogo

gosudarstava, Gudavičius, Mindaugas).

7. See, for example, the work of one of the most prominent proponents of

this assertion, Russian historian M. Liubavskij, Ocherk istoriji

litovsko-russkago gosudarstva.

8. Rowell, Lithuania Ascending.

9. Ibid., 82.

10. Ibid., 294.

11. Norkus, “Ar Lietuvos.”

12. Ibid., 239. This same assertion had been made previously: Rowell,

Lithuania Ascending, 84; Kiaupa, Kiaupienė and Kuncevičius, Lietuvos

istorija, 103-104; Kiaupa, The History of Lithuania, 43-44.

13. Norkus, “Ar Lietuvos,” 240-243.

14. Rowell, Lithuania Ascending, 149-188.

15. Kiaupienė, “Mes, Lietuva,” 9.

16. Detailed studies of the functions of the state in the Republic of

Both Nations have been done by Lappo, Lietuva ir Lenkija, and

Šapoka, Lietuva ir Lenkija.

17. Bardach, O Rzeczpospolitą, 27-63.

18. Examples of some of the titles of the works are: Jerzy Lukowski,

Liberty’s Folly: The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the

Eighteenth Century, 1697-1795 (London, 1991); Robert I. Frost, After

the Deluge: Poland-Lithuania and the Second Northern War, 1655-1660

(Cambridge, 1993); Andrzej Sulima Kamiński, Republic vs. Autocracy:

Poland-Lithuania and Russia, 1686-1697 (Cambridge, 1993); Gerhard

Schulz, Das Polnisch-Litauische Königreich: Machtverfall und

Teilung (München, 1995); Daniel Stone, The Polish-Lithuanian

State, 1386-1795 (Seattle and London, 2001); Richard Butterwick, ed.,

The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context, c. 1500-1795

(Palgrave, 2001).

19. Lebedys, Lietuvių kalba, 98-102, provides the following data regarding

the year of the edition printed at Vilnius University and the number of

copies sold: 1776, 560 copies; 1777 – 1,300; 1778 –

1,260;

1779 – 725; 1780 – 1,150; 1781 – 1,120;

1782 –

1,810; 1783 – 798; 1784 – 365; 1785 –

730; 1786

– 550; 1787 – 100; 1788 – 935; 1789

– 360; 1790

– 2,800.

20. The Lithuanian texts of the 1794

uprising’s manifestos were reprinted in Juozas Tumelis, ed.,

Tado

Kosciuškos sukilimo (1794) lietuviškieji

raštai.

21. A synthesized view of 19th-century Lithuanian history is found in

Aleksandravičius and Kulakauskas, Carų valdžioje. I relied on this work

in writing about the 19th-century developments in Lithuania, though my

interpretation of certain aspects differs.

22. Aleksandravičius and Kulakauskas, Carų valdžioje, 151-152; Genzelis,

“Lietuvos ateities,” 65.

23. Maciūnas, Lituanistinis sąjūdis.

24. Aleksandravičius and Kulakauskas, Carų valdžioje, 176-190; Merkys,

Motiejus Valančius.

25. The national aspect of the 1905 revolution is discussed in Tyla,

1905 metų, and in Motieka, Didysis Lietuvos seimas, the most recent

monograph on the Great Assembly (Seimas) of Vilnius.

26. Trumpa, Lietuva XIX amžiuje, 124.

27. See, for example, the assertions of Arvydas Šliogeris:

“ …in olden Lithuania a political class did exist,

but

again, its influence in the creation of modern Lithuania is nil. By the

seventeenth century this class already had split away completely from

its tribal Lithuanian substrate, while the Grand Duchy of Lithuania had

put down its roots into the Polish rather than the Lithuanian ethnic

body. The Lithuanian tribal substratum out of which the modern

Lithuanian state and the Lithuanian nation emerged existed outside the

boundaries of the Rzeczpospolitą (the Republic of Both Nations

–

Z. K.) as a political entity. And then, Czarist Russia occupied the

Grand Duchy and took away the political power of the former body

politic as well. Now the “Northwest Territory” was

ruled by

Russian bureaucrats. The state of olden Lithuania (more precisely

– of Poland) was destroyed once and for all”

(Šliogeris, Mažvydas ir Lietuva).

28. The declaration of Feb. 16, 1918, was proclaimed publicly for the

first time on Feb. 19, 1918, in the newspaper Lietuvos aidas.

WORKS CITED

Aleksandravičius, Egidijus, and Kulakauskas, Antanas. Carų valdžioje. Lietuva XIX amžiuje. Vilnius: Baltos lankos, 1996.

Baranauskas, Tomas. Lietuvos valstybės ištakos. Vilnius: Vaga, 2000.

Bardach, Juliusz. O Rzeczpospolitą Obojga narodów. Warszawa: Krajowa Agencja Wydawnicza, 1998.

Bieniak, Janusz. “Wyprawa misyjna Brunona z Kwerfurtu a problem Selencji,” Acta Baltico-Slavica, 1969, Vol. 6.

Genzelis, Bronius. “Lietuvos ateities perspektyvų analizė XIX a. Viduryje,” Problemos, 1970, No. 2.

Gudavičius, Edvardas. “Šv. Brunono misija,” Darbai ir dienos. 1996, Vol. 3(12).

______. Mindaugas. Vilnius: Žara, 1998.

Kiaupa, Zigmantas. The History of Lithuania. 2nd ed., Vilnius: Baltos lankos, 2005 (first ed., Vilnius, 2002).

Kiaupa, Zigmantas, Jūratė Kiaupienė, and Albinas Kuncevičius. Lietuvos istorija iki 1795 m. 3rd ed., Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos institutas, 2005, (first ed., Vilnius, 1995; 2nd ed., Vilnius, 1998).

Kiaupienė, Jūratė. ‘Mes, Lietuva.’ Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštystės bajorija XVI a. (viešasis ir privatus gyvenimas). Vilnius: Kronta, 2003.

Lappo, Ivanas. Lietuva ir Lenkija po 1569 m. Liublino unijos. Kaunas, 1932.

Lebedys, Jurgis. Lietuvių kalba XVII-XVIII a. viešajame gyvenime. Vilnius: Mokslas, 1976.

Leonavičiūtė, Inga. “Trys ar keturios šv. Brunono misijų šaltinių versijos?” in Tarp istorijos ir būtovės. A. Bumblauskas and R. Petrauskas, eds. Vilnius: Aidai, 1999.

Liubavskij, Matvej. Ocherk litovsko-russkago gosudarstva do liublinskoj uniji vkliuchitel‘no. Moskva, 1910.

Łowmiański, Henryk. Studija nad początkami społeczeństwa i państwa litewskiego. T. 1-2, Wilno, 1931-1932.

Maciūnas, Vincas. Lituanistinis sąjūdis XIX amžiaus pradžioje. Kaunas, 1939.

Merkys, Vytautas. Motiejus Valančius. Tarp katalikiškojo universalizmo ir tautiškumo. Vilnius: Mintis, 1999.

Motieka, Egidijus. Didysis Vilniaus seimas. Vilnius: Lietuvos istorijos instituto leidykla, 1996.

Norkus, Zenonas. „Ar Lietuvos Didžioji Kunigaikštija buvo imperija?” Lietuvos Didžiosios Kunigaikštijos tradicija ar paveldo ‘dalybos’. A. Bumblauskas, Š. Liekis, G. Potašenko, eds. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2008, 205-261.

Pashuto, Vladimir. Obrazovanije litovskogo gosudarstva. Moskva: Izdatel‘stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR, 1959.

Paszkiewicz, Henryk. The origin of Russia. New York, Philosophical Library, 1954.

Rowell, Stephen C. Lithuania ascending. A pagan empire within East-Central Europe 1295-1345. Cambridge: University Press, 1994.

Savukynas, Bronys. “Nomina propria in causa martyrii S. BrunonisQuerfordensis,” in Tarp istorijos ir būtovės. Vilnius: Aidai, 1999, 13-18.

Šapoka, Adolfas. Lietuva ir Lenkija po 1569 m. unijos. Kaunas, 1938.

Šliogeris, Arvydas. “Mažvydas ir Lietuva,” Literatūra ir menas. 15 February 1997.

Tyla, Antanas. 1905 metų revoliucija Lietuvos kaime. Vilnius: Mintis, 1968.

Trumpa, Vincas. Lietuva XIX amžiuje. Chicago: Algimanto Mackaus knygų leidimo fondas, 1989.

Tumelis, Juozas (ed.). Tado Kosciuškos sukilimo (1794) lietuviškieji raštai. Vilnius, Žara, 1997.

Voigt, H. G. Brun von Querfurt. Mönch, Eremit, Erzbischof der Heiden und Märtyrer. Stuttgart: 1907.

Zinkevičius, Zigmas. Lietuvių kalbos istorija. Vol. 1: Lietuvių kalbos kilmė. Vilnius: Mokslas, 1984.